(Catmando / Shutterstock.com)

By day, he’s a dentist, with a surgery practice in Sharon, Connecticut. But Doctor Martin Nweeia, as Hakai Magazine, a publication focusing on coastal science and scientists reveals, has a leisure-time passion for some of the most unusual teeth on the planet: narwhal tusks.

Nweeia is something of a polymath, a person with broad interests and knowledge. Besides his dental practice, he has degrees in English and biology, and a side interest in zoology and anthropology, and has composed music for documentary films. He has also become an authority on narwhals, as the Narwhal website details.

Having relied on the insights of Inuit indigenous people, Nweeia continues to emphasize the value of collaboration with them in narwhal scientific research.

The allure of Narwhals

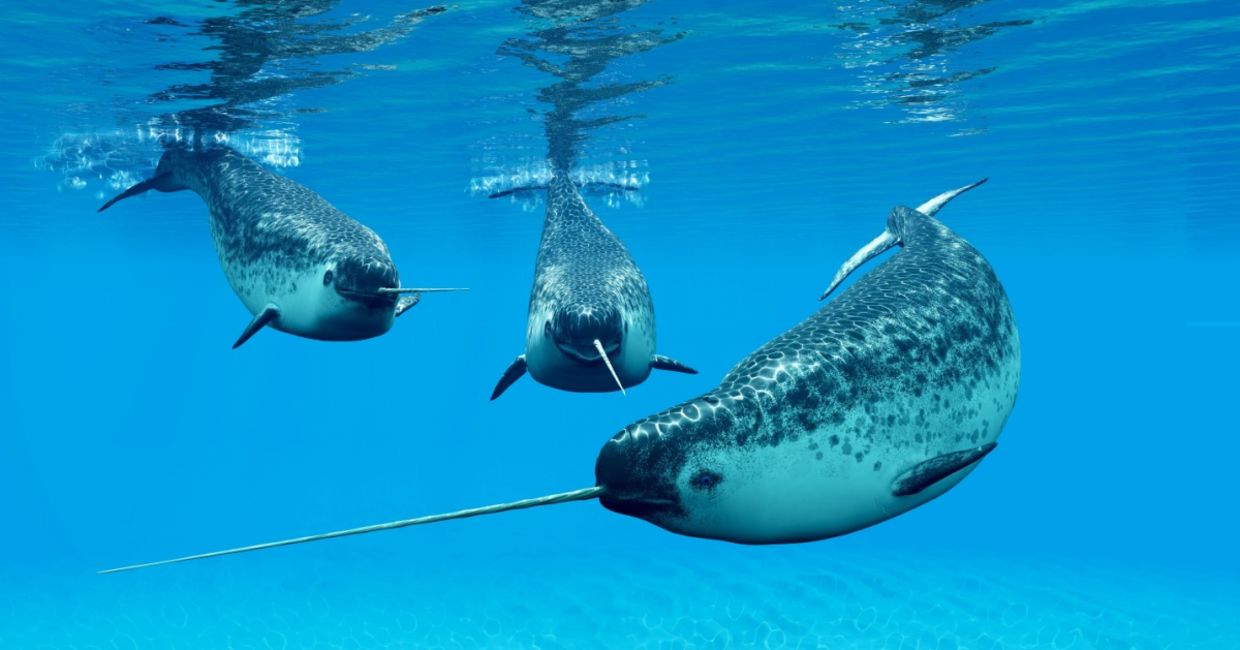

Narwhals, non-migrating whales found in the Arctic waters of Canada, Greenland, Nordway, and Russia, are, as WWF explains, often dubbed the “unicorns of the sea.” This is because males in particular, typically have one or two spiraled tusks jutting out of their heads that can grow to 10 feet (three meters)long!

These tusks are actually enlarged teeth with sensory capabilities, though their function has been a mystery for centuries.

The roots of this dentist’s narwhal passion

As dentist Nweeia tells Hakai Magazine, his fascination for topics beyond classic dentistry, harks back to the time he was about to start dental school, and when he already had a real interest in anthropology, which saw him take moulds of the teeth of Ticuna Indians in the Colombian Amazon.

In his first year of dental school, he gave talks on dental anthropology, in which he discussed animals: “One of the animals that came up, obviously, was the narwhal,” he shares.

As his studies progressed, he was intrigued by how the properties of the narwhal tusk defy the principles he was learning at college. For instance, due to the narwhal diet of some large fish, it has the capacity to produce more than a dozen teeth in its mouth. Instead, it genetically shuts this off. To give another example, all mammals, both females and males, have teeth patterns that are symmetrical, but male narwhals have long tusks on their left side, while females typically do not have a tusk.

This intrepid dentist-in-the-making didn’t accept the prevailing theory that male narwhals had a huge tusk just for social clout, rather like a lion’s mane, or a peacock's tale.

A Millennial lightbulb moment

Around the year 2000, Nweeia decided to devote himself to narwhal research during his downtime. He journeyed to Canada’s Baffin Island, and was introduced to the late David Angnatsiak, the area’s renowned Inuit hunter and head of search and rescue.

The Inuit, as the Alaska Native Language Center explains, are the indigenous people of Alaska and across the Arctic. Angnatsiak shared his rich, experience-based insights with Nweeia, also enabling the dentist to spend time with these whales, which brought real advantages. For instance, the tusk is hard to see, as the whales don’t always point it upwards, and only hours spent with them will give researchers this privilege.

In addition, because the Inuit are legally permitted to hunt these whales for subsistence, Nweeia had access to remnants, which he could sample for further anatomical research back home involving CT scans and electron microscopy.

View this post on Instagram

One finding of his research, he tells Hakai Magazine, is that unlike human teeth, narwhal tusks are soft and flexible on the outside, and much harder inside, where the nerve is.

Significantly, this Connecticut dentist shares, current evolutionary evidence shows that teeth are derived from fish scales which were sensitive to external factors such as temperature and the presence of salt, though we’ve evolved to use our teeth for chewing and biting: “But as we know from going to a dentist, our teeth can sense pain and temperature. After all, they were originally sensory organs, ” he points out.

In 2005, Nweeia suggested that the tusk is a sensory organ after his team discovered that a large section of the tusk features about 10 million sensory connections to its ocean environment. In 2014, he was able to demonstrate this when working with Fisheries and Oceans Canada. After capturing a narwhal for a short 30 minute period to measure its brain and heart activity in response to the exposure of part of its tusk to salty or fresh water, he showed that salty water led to a higher heart rate.

Next research steps

Going forward, Nweeia wants to focus on genetics, now that scientists have a reference genome for the narwhal.

Other interests this dentist would like to explore are what’s called “ocean osteoporosis,” a phenomenon happening as the ocean absorbs more carbon dioxide, making it harder to form calcium carbonate needed to create shells, for instance. He is also investigating the impact of nanoplastics on animals in the Arctic.

Meanwhile, this Sharon dentist continues to serve his local humans so he can sustain his work on these majestic Arctic creatures. As he tells Hakai Magazine: “I’m in my office now; you can come back and have your teeth done. It keeps a roof over my head, keeps myself fed. It funds the passion.”

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE:

This Man Turned His Life Around to Help Turtles

Reclaiming Lost Smiles

Pianist Uses Classical Music to Calm Elephants