This Implant Could Restore The Voices of People Who Lost Theirs

Scientists have created a device that can turn brain signals into synthesized speech.

People say you don't know what you've got until it's gone. This old adage has proven to be true over and over again. Especially for the most basic human abilities, we rarely appreciate the wonder that is our body.

Science is making progress left and right in giving people back lost abilities. One of the latest achievements comes for people who have lost the ability to speak due to neurological conditions like strokes, Parkinson's Disease, and ALS. In these cases, the brain still sends signals, but the body can't transform them into speech.

Neuroscientists at the University of California San Francisco are looking to use those signals to bring these people's voices back.

They have designed a state-of-the-art brain-machine interface that can generate natural sounding synthetic speech from a patient's brain signals that are usually sent to the lips, tongue, jaw, and larynx, according to a USCF press release.

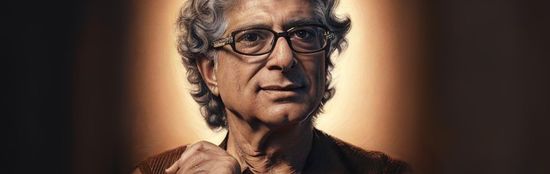

Today, people who have lost their voices due to illnesses can spell out what they want to say letter by letter using devices that track eye or facial movements, but this is very slow, limited to about ten words a minute, and very artificial sounding. The new device designed by Dr. Edward Chang is set to change this.

“For the first time, this study demonstrates that we can generate entire spoken sentences based on an individual’s brain activity,” said Chang, a professor of neurological surgery and a member of the UCSF Weill Institute for Neuroscience in the study. “This is an exhilarating proof of principle that with technology that is already within reach, we should be able to build a device that is clinically viable in patients with speech loss.”

This research built upon a previous study led by Gopala Anumanchipalli, Ph.D., a speech scientist, and Josh Chartier, a bioengineering graduate student in Chang's lab that researched how the brain's center coordinates all the movements needed for fluent speech.

“The relationship between the movements of the vocal tract and the speech sounds that are produced is a complicated one,” Anumanchipalli said. “We reasoned that if these speech centers in the brain are encoding movements rather than sounds, we should try to do the same in decoding those signals.”

The latest study used five volunteers from the UCSF Epilepsy Center with normal speech who had electrodes temporarily implanted in their brains in order to map the source of their seizures before neurosurgery. The volunteers, according to the press release, were asked to read hundreds of sentences aloud and the researchers recorded the brain activity from the region that is involved in language.

This research was used to map a vocal tract that could be controlled by brain activity. This was done by using two neural network machine learning algorithms: a decoder that transforms the brain activity and a synthesizer that converts the vocal tract movements into a synthetic approximation of the person's speech. The accuracy depended on the number of words used and how challenging the words are.

“We still have a ways to go to perfectly mimic spoken language,” Chartier said. “We’re quite good at synthesizing slower speech sounds like ‘sh’ and ‘z’ as well as maintaining the rhythms and intonations of speech and the speaker’s gender and identity, but some of the more abrupt sounds like ‘b’s and ‘p’s get a bit fuzzy. Still, the levels of accuracy we produced here would be an amazing improvement in real-time communication compared to what’s currently available.”

Research in approving the accuracy is still ongoing. The next test for the new technology is to use it with people who can't speak anymore to see if they can use it to say what they want to say accurately.

“People who can’t move their arms and legs have learned to control robotic limbs with their brains,” Chartier said. “We are hopeful that one day people with speech disabilities will be able to learn to speak again using this brain-controlled artificial vocal tract.”

While the voice interface is still in its infancy and could take a while to mature, the goal of restoring voices to people who have lost theirs is almost miraculous. This could help people not only improve communication but could also make them feel less isolated and more connected to the world.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE:

Project Revoice Gives People With ALS Their Voice Back

7 of the Best Apps for People with Disabilities

Michael J. Fox Just Made a Huge Contribution to Parkinson's Research