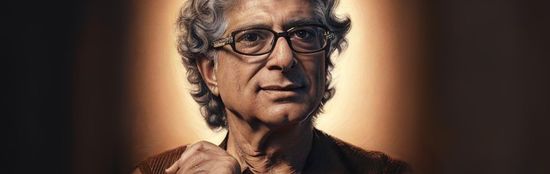

Painted wooden crosses in the famous Merry Cemetery in Maramures, Romania. (Danilovski / Shutterstock.com)

Romania is much more than just vampires in Transylvania. There’s sci-fi themes parks in underground salt mines, an ethereal waterfall full of moss, mock Hollywood signs, and ridiculously windy stretches of road (seriously, think 60 kilometers of elevated hairpin turns).

There’s also Cimitirul Vesel, the world’s happiest cemetery.

The Merry Cemetery is more an open-air tourist attraction than a graveyard, and the Romanians’ down-to-earth nature leaves visitors laughing in the face of death. Playful, historic and tucked away, this gem bridging life and death provides an intimate look at the country’s true nature.

Nestled at the base of the towering Carpathian Mountains is S?pân?a, a little town frozen in time. Men in horse-drawn carts work the fields, women wearing dark scarves knead dough and barefoot children spin tops in dirt roads. Their lives might seem common, but their burials are nothing short of colorful.

Since 1935, more than 1,500 of S?pân?a’s residents have been buried under Stan Ion Petras’ brightly-painted wooden crosses. At age 14, Petras joined the region’s ranks of woodcarvers, but focused on his own artistic invention. All hand-carved and hand-painted, the slender crosses of Cimitirul Vesel come with a personalized epitaph in poem format and an amusing illustration.

The paintings depict the deceased either at their moment of death or partaking in their favorite activity. The inscriptions are short and direct, following the ideology that “there’s no hiding in a small town.” As a result, there’s inscriptions about alcohol, laziness and whimsical dreams. While others scowl upon making jokes about the deceased, Petras spent days eavesdropping around town, on the hunt for juicy gossip, which, in turn, served as witty eulogies.

For example:

Under this heavy cross,

lies my poor mother in-law.

Three more days she would have lived,

I would lie, and she would read (this cross).

You, who here are passing by,

Not to wake her up, please try.

Cause’ if she comes back home,

She’ll criticize me more.

But I will surely behave,

So she’ll not return from grave.

Stay here, my dear mother in-law!

The Merry Cemetery continues to expand, thanks to Petras’ most skilled apprentice, Dumitru Pop Tincu. While the successor’s color palette has evolved a bit, many of the original color associations and symbolic motifs are used as homage to both Roman textile designs and Petras’ use of natural dyes. To him, blue represented the freedom of the sky and provided a cheerful passage to the other world.

This quirky take on death stretches back to Dacian customs, whose culture dominated the area until Roman invasion. Believing in life after death, the Dacians viewed death as just another adventure that would bring them to Zamolxes, their ultimate god. This light-hearted spiritual journey is a stark contrast to the pain-filled perspective of death characteristic of Eastern European religions.

Today, a celebration of the Merry Cemetery and death itself is continued not only in the cerulean crosses, but also in a festival of song and dance that takes place in August. This Festival of Maramure? Traditions is filled with folk music and patterned costumes, fiddles sawing away and skirts twirling long into the night. After two days of local artisans showing off their weaving, pottery and wood carving (and endless cheese tasting), guest artists from other countries go onstage to present their interpretations of the cemetery’s epitaphs.

When visiting, take a few extra days to explore the Maramure? region, where century-old traditions are reflected in everyday life and tipi haystacks dot the landscape. Since four-fifths of the area is still covered by forest, intricate woodwork is present not just in Cimitirul Vesel, but also in many door decorations of tall-steeple churches and handcrafts.

Enjoy the warm hospitality, bond over a few shots of pálinka and earn yourself a worthy epitaph for when the time comes!

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE:

14 Reasons Why Travel Changes Everything

9 of the Most Fascinating Places on Earth

5 Awe-Inspiring Travel Destinations For Your 2017 Vacation

This article by Julia Zaremba was originally published on The Culture-ist, and appears here with permission.