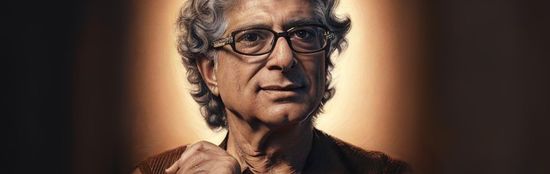

(pixelheadphoto digitalskillet / Shutterstock.com)

BY EDEN PONTZ

When Ellen Galinsky was trying to come up with a title for her massive research project and book about adolescence, The Breakthrough Years seemed fitting. After all, adolescence is a true “breakthrough” time when the brain is developing rapidly and is particularly sensitive to environmental influences. It’s when we seek new experiences, build and strengthen connections, and form essential life skills we will use in the future.

Since the founding of the field of adolescent development in 1904, researchers have viewed adolescence as a time of “storm and stress.” But our expectations — negative or positive — affect how teens behave. That’s why Galinsky believes it’s important to reframe our understanding of adolescence from negative to positive—from dread to celebration.

Across more than nine years, Galinsky surveyed more than 1,600 tweens and teens between the ages of nine and 19 and their parents, asking them what they want to tell adults about people their age. She hopes parents and caring adults will take their messages seriously.

Understanding the teenage brain

Eden Pontz: You’ve curated a series of five main messages from young people that they feel are key for adults to understand about them. What are they?

Ellen Galinksy: The first message from young people is “Understand our development.” In our nationally representative survey, we asked parents, “If you had one word or phrase to describe the teen brain, what would that be?” Only 14 percent of the parents used positive words about the teen brain. The most frequently used word by 11 percent of the parents was “immature,” and another 8 percent used similar words. Far too many of us are seeing adolescents as deficit adults. We wouldn’t say a toddler is a deficit preschooler. But we see adolescents as “not adults.”

Adolescents need to be explorative and have adventures. You need to be able to react quickly and know if a situation is safe or not. That’s what they need to do to survive. Much of adolescent research has been on negative risks, like taking drugs, drinking, and making what are often called “stupid decisions.” People wonder, “Do adolescents make these decisions because they feel they’re immune from danger?” That’s not true. Research by Ron Dahl from the University of California at Berkeley has found that when young people are doing scary things, they’re more attuned to danger. They’re learning to go out into the world — to move out and be more on their own. He describes it as “learning to be brave,” a characteristic that’s admired around the world.

How to talk to your teen

The second message is “Talk with us, not at us.” Adolescents need to have some agency—to learn how to make decisions for themselves. I don’t mean to turn everything over to them—but to find an appropriate level of autonomy. They’re right in saying, “Don’t just tell us what to do.” As one young person said, “If we’re the problem, then we need to be part of the solution.” The best parenting, the best interventions, and the best teaching involve adolescents in learning to solve problems for themselves, not having problems solved for them.

The third message is “Don’t stereotype us.” Thirty-eight percent of adolescents wrote sentiments like we’re not dumb, we’re smarter than you think, we’re not all addicted to our phones and social media. Don’t put us all in a big group and say we’re the “anxious or depressed generation” or the “entitled generation,” or the “COVID generation.” Let us be the individuals that we are. Research shows if we expect the worst, we sometimes get the worst. When parents’ views of the teen years were negative — 59 percent of parents had negative words to use about teens’ brains — their own children weren’t doing as well. They were more likely to be sad, lonely, angry, or moody.

The fourth message from adolescents is “Understand our needs.” There’s a stream of research in psychology called the “self-determination theory.” This theory suggests we don’t just have physical needs for food, water, and shelter; we also have basic psychological needs. These needs include having important relationships or caring connections, feeling supported and respected, having some autonomy, and finding ways to give back. I found the kids who had those basic needs met by the relationships in their lives before the pandemic did well during the pandemic.

The fifth message is “We want to learn stuff that’s useful.” That speaks to the importance of executive function skills. People who have these skills are more likely to do well academically, in health, wealth, and life satisfaction, than people who don’t. These are skills like understanding others’ perspectives, goal-setting, communicating, collaborating, or taking on challenges. They’re skills that build on core brain processes that help us thrive.

EP: In the second message, you say adolescents don’t want to be “talked at.” What does that look like, and why does it cause conflict?

EG: We’re likely to talk “at” adolescents versus “with” them for several reasons. The first is that we forget what it’s like to be an adolescent. It’s called “the curse of knowledge.” It’s like a doctor talking to you about a medical condition. The doctor assumes you know what they’re talking about, but you haven’t a clue. It’s because it’s hard for us to not know what we already know.

The second reason is they can look like adults so we can see them like adults.

There’s still another reason why adolescents don’t like to be talked “at.” Teens need some autonomy. Autonomy doesn’t mean complete control. It means being choiceful and feeling you are in charge of your life to some degree. We all need that, but adolescents particularly need it because they know their parents will not always be there.

EP: Instead, adolescents want to be talked “with.” What does that look like?

EG: The research on autonomy support is very useful here. I call it a “skill-building approach.” It includes the following: 1) Checking in on ourselves because our feelings can spill over into how we handle challenges. 2) Taking the child’s view and understanding why they might be behaving how they’re behaving. 3) Recognizing that we’re the adults so we need to set limits. Everybody needs expectations and guidance in their lives. Nobody wants to be without guardrails. 4) Helping adolescents problem-solve solutions.

What does problem-solving look like? Here’s an example—“shared solutions.” I’ve used this approach as a teacher and as a parent. If there’s a problem—for example, kids aren’t keeping their curfew, homework isn’t getting done, they’re on their devices, or they’re disruptive in class—you state the problem and what your goals are. Then, you ask the young people to suggest as many solutions as possible. They can be silly ideas, they can be wonderful ideas, you can even get jokey about it.

Then you go through each idea and ask, “What would work for you in that idea? What would work for me?” You are helping adolescents to take your perspective. Next, you come up with a solution to try together. Now you both own that solution. If you need consequences, that’s when you establish them — not in the heat of the moment. Finally, you say, “This is a change experiment. We’re going to see if it works.” You try it out. And if it does work, great. It probably will for a while, but when it needs changing, you go through the shared solutions process again.

EP: What are some things we do that may send unintended messages to adolescents, that leave them feeling unseen or unheard? And what can we do instead?

EG: The late child psychiatrist Dan Stern once said, “Every human being wants to feel known and understood.” It isn’t just our children or younger people. It’s all of us.

I asked some open-ended questions in my study. One of them was, “If you had one wish to improve the lives of people your age, what would it be?” A number of young people wrote about the things that made them feel unseen, unheard, and not understood — statements like “Get over it,” “You’ll grow out of it,” “Stop being such a teen,” or “It’ll get better.” To them, statements like those made them feel that the adults in their lives weren’t understanding, weren’t taking their problems seriously. We’re better off if we try to understand what our kids are trying to achieve with communication before we respond to it.

EP: What are things parents can do to ensure their child knows they are supported and a priority?

EG: Here’s an example from my own life. My daughter was upset at my grandson for loving technology as much as he does. And she told him so in no uncertain terms. He said, quietly under his breath, “But you’re on it all the time, too.” And he was absolutely right.

We had a family meeting where he told his mom how he felt, with her acting one way to him and living another way. And she listened to him and was more mindful of how she used technology. That made a big difference in their relationship. So many young people wrote in, “We see you,” or “You think we don’t understand, but we’re watching you,” or “We’re learning from what you’re doing, not just what you’re saying.” At our best, we need to live the way we want them to live.

Discover more from our conversation with Ellen Galinsky at parentandteen.com.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE:

This Library Gives Kids and Teens Books for Summer Reading

Lost Voices Empowers Teens to Find Their Voice through Music

Activism Can Improve Wellbeing in Teens